This section features short essays by invited guest writers.

Welcome to our latest Sound Journal entry by visual artist and improvising musician Fergus Kelly. Fergus has become quite a regular contributor to this project over the past few years and we have been fortunate to include his valuable field recordings in the Lost Sounds and Guest Recordist sections of A Sound Map of Dún Laoghaire. We hope you will enjoy reading his essay.

Fog bell at the East Pier Battery, Dún Laoghaire

19/10/2021

Everybody Hears The Hum At 3am*

Sound marks, memory prompts and possible futures.

By Fergus Kelly

* * *

Growing up in the leafy suburb of Glenageary in south county Dublin in the 70s and 80s, certain sounds in the landscape captured my imagination and established a presence that became part of my sense of place.

The most salient and memorable of these was the foghorn that bellowed out from the East Pier in Dún Laoghaire. Like a slow motion impulse response, it described a sense of the space it occupied as it reflected off surrounding surfaces, with a hollowed out, widescreen sense of dimensionality. It also had a mournful and vaguely feral character, sounding not unlike a large mammal yawning, ceasing as it reached the end of its breath. It really got the hook in me from an early age, its acoustic footprints extending for miles around, seeping into the landscape like a kind of haunting.

You can hear a recording of the East Pier foghorn by clicking here

Thankfully I had the presence of mind to make a recording of it in 1987, not long before it disappeared from the landscape, to be replaced by a harsher blast with none of the character of the older foghorn.

Another kind of haunting in the bay occurred when Dorothy Cross had her Ghost Ship installed for a spell in 1999, its spectral form appearing and disappearing with onboard illumination periodically charging its skin of phosphorescent paint. An IMMA/Nissan public art project using a decommissioned lightship, it was a wonderfully simple idea, beautifully realised, that left a lasting impression.

Reduction or absence of sonic reference points in the landscape are as affecting as key sound marks (sonic landmarks). An eerie silence descends in a solar eclipse when birdsong simply stops, as some of their reference points are scrambled. Walking the East Pier in Dún Laoghaire was a regular activity growing up, and on one especially memorable occasion I ventured out in heavy snow. When I reached the pier there was no-one else there and the snow lay thick and undisturbed. The landscape felt sonically muffled. I've always found that compressed crunching sound of walking in heavy snow immensely satisfying. You're not entirely on solid ground, but you're not floating or in water either, but treading a temporarily solidified yet volatile form of it.

As I walked further down the pier, I heard a subtle crackling noise above me. Looking up, I noticed what seemed to be a static charge flickering at the tops of the lamp posts, somewhat like the putter of a lowered gas cooker flame, but more agitated. After a while, the clouds lifted a bit and the charge disappeared, only to reappear sometime later as the clouds gathered again. Out there alone along that long rocky outcrop, it felt like a strange visitation of sorts, which intrigued me. An added bonus in the pleasure of the walk, swaddled heavily as I was against the bitter cold, wreathed in clouds of my exhaled air.

The now absent spinning anemometer was part of my experience of the pier in those days, and it makes an appearance in a moment of epiphany in Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape, a mirror of his own epiphany transplanted from its origin in Greystones. I really like the fact that this is commemorated in a plaque set into the wall directly below the anemometer, on the lower section of the pier, with the quote from the play:

“...great granite rocks the foam flying up in the light of the lighthouse and the wind gauge spinning like a propeller, clear to me at last...”

East Pier and Ringsend Towers.

Another memorable event on the East Pier was in the summer of 1982 when Dublin band 9 Out Of 10 Cats did a gig on the bandstand to a large appreciative crowd. A great set on a beautifully balmy evening. The only band I ever saw perform there, as far as I can remember, but a lovely commingling of community, weather, Victorian architecture and music – a unique moment in time, a cherished memory.

Before the advent of cheap flights, Dún Laoghaire harbour was also a point of departure for dreaded trips to London in the 1980s between years in art school, to take up summer jobs in the absence of any local work in our recession-hit economy. It seems hard to imagine that a trip that now takes about an hour, essentially took an entire working day as you set off on the ferry at 9am, reached Holyhead in Wales three hours later, then spent about another 4 hours or so on a train down to London, arriving exhausted and disheveled after traveling in cramped conditions for such an extended period. Those summers stretched out interminably, a lonely and homesick experience for me, heightened by being of a shy and retiring nature, I tended not to mix and meet others, just did my own thing on days off – trawling galleries and record shops and bookshops. Concerts as well, of course. The small rewards that kept me going. Always arriving home with a case heavy with LPs, most of which would never grace Dublin record shop shelves at the time. These were investments in my continuing musical education.

My first foray into field recording began in London with the purchase of a secondhand recording walkman from a small shop in Tooting, which I think I paid about 60 quid for. It had a great stereo clip mic that I could attach discretely to my clothes, thereby avoiding the nerd factor of pointing a mic at whatever I was recording, inevitably drawing unwanted attention to myself. It looked like I was simply listening to music - perfect. The first experience of recording was revelatory: entire worlds rich in detail, incident and dynamic unfolded between my headphones. Everything was interesting. I was smitten.

Amongst various ear opening gigs I attended in London at this time, one of the most impressive was seeing the Bow Gamelan doing a performance with Bob Cobbing in the ICA in 1986, an opera commission which they called In C and Air. Amongst its many wonders, was a Renault 4 suspended from an aerial rig, which moved across the stage, whilst its boot flapped open and shut. The company responsible for realising this wonderful spectacle were appropriately called Miraculous Engineering. Another memorable moment was when Paul Burwell went waist-deep into a tank of water built into the stage, drumming metals whose tone pitch-bended as Anne Bean and Richard Wilson dipped them in and out of the water.

To see photos of Bow Gamelan performing their opera In C And Air, with sound poet Bob Cobbing click here

The only other time I saw the Bow Gamelan was when they took part in the Dublin street carnival in 1990, amidst a flurry of World Cup fever, playing on a pontoon beneath the Ha'penny Bridge. This was plagued by a car alarm that went off on the quays just before the gig and continued throughout, despite the strenuous efforts of Paul and z'ev (replacing pregnant Anne Bean) to disarm it. I'm really glad I had the opportunity to meet Paul, he was an inspirational figure. We sunk a few pints in The Norseman between set-up and showtime and attended a fireworks display at the Custom House the following night, where he gave me a copy of the only LP of Bow Gamelan's work, Great Noises That Fill The Air, on Hugh Metcalfe's Klinker Zoundz label. One firework display crackled and spat to reveal a familiar face. “Oh look” said Paul, “it's Jack Charlton.”

Anne Bean gave me the Cold Spring CD reissue of this LP when I met her for the first time in person in 2019. I was over to see the last UK show of the recently reconvened/expanded version of This Heat, which was staggeringly good. She invited me to take part in a series of live events the following year on the Thames foreshore at Limehouse Reach, called Come Hell Or High Water. The pandemic put paid to me traveling, so a soundwork, Spectral Vectors, was created in lieu of an appearance, using some of those first field recordings from 1986, along with BBC archive recordings, other documentary footage and my newer explorations made on recent visits, all connected with the Thames. There's a certain circularity at work here that I find quite satisfying.

To hear Spectral Vectors click here

Other local sounds remembered from the 70s and 80s would be the passing of late night goods trains along the tracks that stretched from Greystones, via the nearby Glenageary station and on into Connolly station in the city centre. A distant spectral presence in the dead of night, humming industrial revenants animating the rails, whilst I lay awake amidst the closer presence of leaves rustling on nearby mature trees. Sometimes I would leave my bedroom curtains open at night, and one unforgettable night in 1985 a huge thunderstorm passed through for what seemed like an age, my bed a great ringside seat for a spectacular show. I was sorry to see it go.

Motorbikes would speed down the main road near the back of the house, dopplering loudly as they went, sonically scoring the landscape, a time-stretched impulse response, and a sound which I found particularly evocative. That drone drilled down deep into the very marrow of me, it seemed. After my first summer working in London in 1983 in a pub off Oxford street, a locality with ever present hums, drones and noises at various levels of annoyance, I will never forget the sensation of my first evening back home in Dublin, in my bedroom, and the quiet... the difference was remarkable. The negative space of sound's absence felt flipped to create a full-bodied positive presence. It felt like the air was cushioned. It was delicious. And a profound relief.

An indelible part of growing up in the era I did, especially around the late 70s/early 80s, was the post-punk musical landscape at the time, with its DIY methodology and sense of exploration and possibility - how fresh, new and forward looking it felt, and how well a lot of it has travelled since. 'Futurology' as discussed in magazines like Omni and elsewhere was still 'a thing', in a way that it has long ceased to be in an age where history has collapsed into a restless, impatient and inescapable present, with everything going on everywhere all the time, immediately accessible. A culture cauterized on constant updates and breaking news, society endlessly gorging itself on information shot from a fireman's hose. Pre-mobile phone, going incommunicado for hours at a time – seems unimaginable now.

To hear Dirt Behind The Daydream click here

Tapping into that sense of future excitements (that soon ran dry), and in a pre-echo of the Renault 4 gracing the stage of the ICA, I remember being in a Renault 4 and visiting the recently built Dún Laoghaire Shopping Centre in the late 70s, and the exoticism of parking on the roof ! This was heightened by the rush created by Tubeway Army's Are 'Friends' Electric on the car radio. It was still quite few years before I discovered J.G. Ballard, but looking back, it was all quite Ballardian. This was only the second shopping centre to be built in Dublin, after the one in Stillorgan in 1966, so.. exciting times ! Are 'Friends' Electric's simple siren-like melody re-surfaced in recent times, sampled in the Sugababes song Freak Like Me, a future echo carried like a long-dormant sleeper reactivated, given new life, its presence in their song refiring old synaptic connections, generating a remembered sense of excitement of the original.

%20-%20lithograph%20by%20Odilon%20Redon_new.jpg)

A Mask Sounds The Funeral Knell (1882), lithograph by Odilon Redon

Post-punk music was a portal to other parts of the culture, such was the quality of lyric writing and references in the music. I remember, shortly after Magazine's single A Song From Under The Floorboards came out, going into Eason's in Dún Laoghaire and getting a copy of Dostoyevsky's Notes From Underground (coupled with The Double), that Howard Devoto based the lyric on, an edition with a wonderful Odilon Redon lithograph, A Mask Sounds The Funeral Knell (1882), on the cover. Magazine also used Redon's images on their Shot By Both Sides and Give Me Everything singles and their final album No Thyself.

Eason's in O'Connell street once housed a record department in its basement, and one of the curious little bits of ephemera from that time that has stuck with me was how they used to put little yellow stickers on the corners of the open end of the inner bag of the LP with the words 'guaranteed unplayed' printed on them. A curious claim to quality of grooves unvisited by needles, lending perhaps an unintentional irony to Neil Young's The Needle And The Damage Done, perhaps? Or, if you don't like the LP it's guaranteed to remain unplayed?

Sound effects LP's, artists' personal archive.

Mac Records, which most Dubliners will remember fondly from his pitch in the George's street arcade, began life in a small upstairs premises near St. Michael's hospital in Dún Laoghaire in 1985. I remember an early visit netted me a copy of one of the Deutsche Grammophon Avant Garde series of LPs featuring Mauricio Kagel and Dieter Schnebel (pub. 1969), and the Turnabout 1966 LP of electronic music featuring John Cage, Ilhan Mimaroglu and Luciano Berio. I had recently read Cage's Silence & A Year From Monday (copies picked up from Foyles in London) and my interest was piqued. Mac was intrigued by my choice and we fell into conversation about my interests, and on subsequent visits he would fish out something he thought might interest me from the 'outer reaches'. I remember getting an LP of BBC Disaster Sound FX that fascinated me, which I made good use of later in my first approaches to tape composition.

Going to school in Belvedere involved half hour train journeys to the city centre, which underscored that sense of separation between city and suburb. Tara street was our stop, and after school, the approaching homeward bound train used to pull into the station with the most ear-shredding squeal of brakes as metal on metal ground loudly to a halt. On the odd occasion when the journey began at the next station, Westland Row (as Pearse Street used to be called), that industrial-grade feedback was greatly amplified and smeared across all the reflective surfaces within the large glass vaulted ceiling of the station. It was quite extreme. It's curious how a somewhat less aggressive version of this sound surfaced later in the form of bowed cymbals and scraped metals in the music of Organum, AMM and others that became a key part of my musical landscape. But it would take a few more years for my ears to accommodate it in that context.

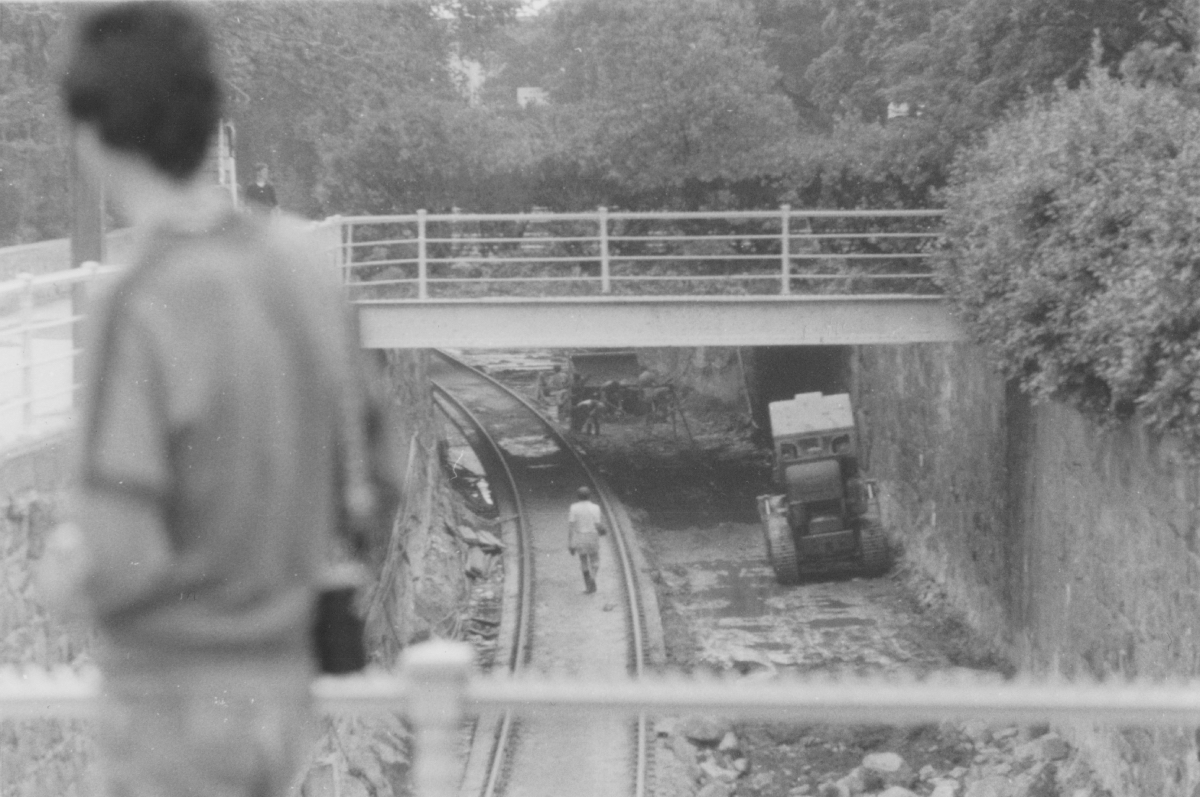

New track laying for the forthcoming Dart line, Dún Laoghaire, c.1981/82. Photo by Paul Kelly.

CIE's rolling stock at the time was mostly comfortable, similar to today's mainline trains, though theirs weren't so clean – I remember the clouds of dust that would belch forth if you whacked the cushioned seats. Occasionally the carriages were quite uncomfortable, and more like something out of Eastern Europe. Cattle wagons, we used to call them. They had plastic office type seats bolted to a structure running below the windows, leaving a wide open space in the middle with a few upright rails to hang onto.

The boredom of one journey home with school friends Kevin and Neil was unexpectedly leavened by a surprise occurrence. Kevin was standing opposite myself and Neil sitting down, as his school bag lay resting against one of the upright poles.

There was an older clerical worker in a grey mac seated opposite us with a leather satchel gripped and held daintily on his lap. He was Brylcreemed and had a pencil mustache. He looked quite like Ron Mael from Sparks. It was hard to tell his age, but might have been in his late 40s/early 50s, which to us youngsters was ancient. Seizing a split second opportunity, he suddenly motioned to myself and Neil with a 'shush' finger to the mouth gesture, whereupon he swiftly stood up, whipped Kevin's bag off the floor and stuck it behind him as he sat back down, staring ahead, deadpan. We were gobsmacked, but kept schtum.

There was an innocent sense of fun about what was unfolding and we just ran with it. When Kevin noticed the absence, he was completely flummoxed, sure that it was us who had hidden it. Ron Mael let it play out a little longer before offering the bag back with a grin to an even more perplexed Kevin. So unexpected and hilarious. This man's impish sense of fun was like a theatrical break in the fourth wall of expected behaviour of people going quietly about their business on a busy train. The daily ritual of traveling from work, brightened by the child in this man that simply broke out for a moment and had a laugh. A treasured memory.

An inescapable sound mark that scored my time in Belvedere was provided by the plaintive call of ever present herring gulls. Flying over the school, their calls would bounce off the buildings and echo around the yard, sounding out the space with their dreary, insistent hectoring. One of them quite literally left his mark on me as the aerially jettisoned excrement splashed down the back of my school blazer, leaving a watery greenish-white paint-like smear. It had the weirdest odour that I can barely describe, except to say that it had a high chemical pong and was more like some cleaning product gone badly off.

Key sounds in the culture come and go with the decades. Amongst the disappeared from my school-going days would be the military-style clack of hard-soled shoes whose heels were strengthened when a cobbler fitted 'tips' – metal inserts in the corners to slow the natural wear imposed by the body's weight and gait. There was a brittle and brutal clarity to that sound that scored your steps that I used to enjoy. Since leaving school though, I don't think I've worn any hard-soled shoes, and much prefer my footwear not to draw such blatant attention to itself. We also had great fun whacking our heels off the concrete to create sparks.

'Clackers' were another item that generated a loud report – two hard plastic balls at the end of strings held with a small plastic fob and tapped together until the gathered momentum meant they eventually hit on the upswing as well. An era of gimmicks, including handshake buzzers, green slime and stink bombs that came in small glass ampoules, which would sometimes rather uncharitably be crunched underfoot in a crowded train, venting a brutally sulphurous pong.

Hey Jimmy, gimme the gimmix

Another day – another fad

Funk, yes, even for a minute.

They’re not bad – dad

From the barmy days of the hoola hoop craze

To the skate board panic of today

Amused, amazed, aghast we gaze

We don’t get in the way

from John Cooper Clarke's, Gimmix (1978)

Skateboards. That's another one. The difference between quality and shoddy boards spelled out when plastic met path with either a loud rattle or a smooth whoosh. I think some of the cheapest boards might've been sold from bargain supermarkets at one stage – very noisy, and slow. I must've saved up some pocket money as I shelled out for a board made of high quality separate components – G & S varnished wooden board with a sandpaper-like strip of grip tape, ACS trucks (axles) and matt candy pink high speed super smooth Kryptonic wheels. I was set ! Much fun was had.

I remember, before I got this board, a chap from a nearby neighbourhood, who was always one step ahead of the game, had put a set of Kryps (as we called them) on one of the cheaper boards, souping it up. Our house was at a fork at the end of a steep incline, and he cut quite a figure, as he whooshed past our front gates, near-noiselessly on his adapted board, hunkered down to reduce drag, one hand lightly gripping the board, the other occasionally gesturing forward for balance as he navigated the path's peaks and troughs, with an army surplus German helmet instead of a regular crash lid, he was the coolest thing on four wheels.

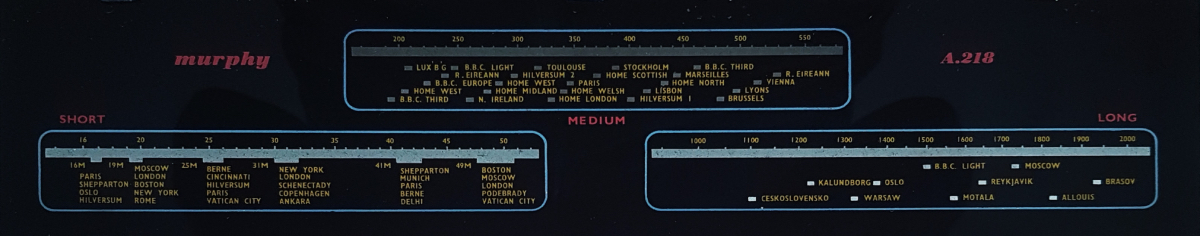

Murphy radiogram front panel, complete with Shepperton typo - what would JG Ballard think?

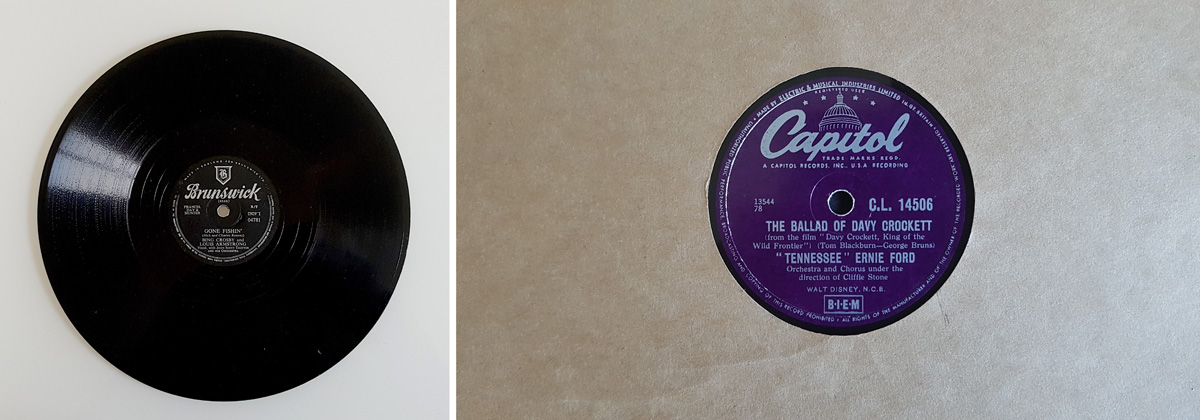

I grew up with records. Or LPs (long players), as they used to be known. Before vinyl, there was shellac, a harder, less flexible material that records (78s) were made of, that spun at 78rpm. My parents had a beautifully crafted Murphy radiogram that played 78s. A dead weight, stand-alone piece of varnished furniture with a flip-top lid that could be cranked to stay open. It had a horizontal radio dial set into the front with a glowing central lamp not unlike HAL, the on-board robot from Kubrick's 2001 (which was actually a Nikon 8mm wide angle lens lit from behind). The 78s were a mixture of classical and jazz that my mother was keen on (Louis Armstrong & Bing Crosby doing Gone Fishin' is one I remember).

Gone Fishin' by Bing Crosby and Louis Armstrong & The Ballad of Davey Crockett by “Tennessee” Ernie Ford 78s, artists' personal archive

The 78s were housed in an ingenious 'lung' of space cut out from the bottom right corner of the radiogramme, with the discs stacked upright, and a door that ran flush with the side panel, which opened and closed with an interior metal grip that clipped open on push, and closed on another push. When my mother was in her mid to late 20s she used to play piano in a group that played a large variety of jazz standards, with a repertoire of up to 70 songs – pretty impressive. There was a piano in the house which got played less and less as we were growing up, until it was eventually dispensed with.

My father wasn't really interested in music, though I seem to remember him liking Janet Baker at one point early on – there was an album of hers in the house. Likely a birthday or Christmas gift, as I have no memory of him ever buying records for himself. His interest was in painting which, in his spare time, he used to do largely au plein air, and had a good facility with. This could have been developed and honed if he had the chance to study at college – not really an option in the late 1930s when he left school.

When my father retired in 1982, he was given a hi-spec music centre (record/tape/radio player). It's only on looking back that it strikes me as an odd choice for someone not especially interested in music. It was a Mitsubishi MC 8000, with an automatically controlled vertical record deck. The logic of this design lay in the fact that the deck's linear tracking playing arm remained at the exact same angle as it travelled across the grooves, thereby eliminating the distortion that supposedly occurs with a regular deck, where the needle's angle gradually shifts as it moves to toward the centre of the disc.

A rare enough thing in the early 80s, as Bang & Olufsen and Rotel were the only other manufacturers to produce these decks at the time – two fairly high end brands. If this was such good quality, and a step up from regular decks, it's curious how it never caught on? Bang & Olufsen was the highest of the high end hi-fis in the 70s and 80s, with its ultra minimal, futuristic design and superior sound quality. A neighbourhood friend's father had a B & O three-in-one, and it was as if it had come from outer space. In fact, it's simple dark, wedge-like form was like a horizontal version of the monolith in Kubrick's 2001.

One aspect of the Mitsubishi that was a great boon to me was the microphone input that allowed you to mix a live source with whatever was playing on the hi-fi. I could combine a tape recording with some live percussion and record it to another tape deck. This recording could be put into the Mitsubishi and the process repeated to build up multi-tracked layers. The quality depreciated significantly the more you bounced between decks with the build up of tape hiss, but before I had access to 4-track recording, this was an exciting way forward to combining sounds in creative ways. I guess the manufacturers were thinking more along the lines of some form of karaoke or DJ function.

The circuitry that controlled the 33/45 rpm deck speeds must've developed a fault as I remember sometimes when you were listening to an LP, it would get momentary accelerations for a second or two as it flipped between the two speeds. The long unused Murphy radiogramme, at a height of about 3 feet, became the default stand for the Mitsibushi, the old technology propping up the new, both long since consigned to the scrapheap.

As a visual artist and improvising musician, I often think of the dual influence of my parents' skills, and feel grateful that these skills have rubbed off on me in some form. I often feel split between the worlds of visual art and music, occupying a nether region between the two it seems, not having properly learnt an instrument and unable to read or write music. Though that is only one system for music-making. My own method, whilst perhaps a bit more labour-intensive and time-consuming, is simply another.

At the same time though, being so heavily invested in listening to music, and drawing considerable sustenance from it (my lifeblood, really), it often strikes me that the simple act of being able to play an instrument with some facility and feeling is a great gift, to simply 'turn one's hand' – it could almost be seen as a form of everyday magic, with its transformative and time-traveling powers.

* from Mark E. Smith's lyric for The Fall's song Prole Art Threat, from the Slates LP (Rough Trade 1981).

All photography by Fergus Kelly except where noted.

06/11/2020

The Sound of Place

By Seán McCrum

* * *

Temple Hill Burial Ground, Blackrock, County Dublin

and The British Cemetry, Kolokotroni 22, Corfu

Temple Hill Burial Ground is in Blackrock, Co. Dublin. The British Cemetery is in Corfu, in Greece. Despite the distance between them, the experience of visiting each one is very similar. Each creates a sense of ease and peace through the thought and work of an individual – in Temple Hill, Christopher Nuzum and in the British Cemetery, George Psailas - who cared enough about their place not only to develop, but to care for and tend it. The sites are similar in size. Each is surrounded by a high wall, which reduces external sound to the benefit of the quietness of the interior.

Both of these individuals have conserved and planted trees and other plants. They have remade pathways which curve around the graves and trees, so that someone coming into the ground is gently led around by the paths themselves and the varied shrubs. The texture and sound of walking on these pathways is central to experiencing each place. The relationship between graves and their natural environment is subtle and balanced.

Climate and environment are different. In Corfu, the summer is hot and dry but very wet in winter. In Ireland, summer and winter are variable. Consequently, trees and plants differ. Shade is very important in Corfu, less so in Ireland. However, in both, light and shade are central to defining a visitor’s experience.

Sound and visual are both central to creating the way in which a visitor engages with each place. As someone walks, the loose stone surface of pathways create texture and sound. Walking activates the subtle sounds of clipped grass or wilder places. Species of trees have been carefully balanced. Even with very slight wind, the trees rustle continuously. This varies from tree to tree; it also changes as an individual moves along a path. As other people walk around, sound moves as they move. Conversation declines as people attune to the place. Birds call. There is the sound of insects. Light and shadow enhance what is growing. Trees differ visually – height, colour of leaves, structure of trunk and branches. Paths curve around the gravestones and trees. They lead from glade to glade.

Burial ground and cemetery each relate to different but specific groups. Temple Hill is a Quaker burial ground and has been used continuously since the first interment there in 1861. The British Cemetery was for British administrators, soldiers and sailors between 1816-1865, when Britain oversaw the Heptanese [the seven islands in the Aegean Sea, including Corfu]. It has been used occasionally since then.

The design and layout of gravestones is very different. They memorialise the individual buried, but with different intentions. In Temple Hill, all of the stones are made with the same material and to a specified standard and simple design, with their texts containing the minimum information about each individual buried. Stones are laid out in lines, with no sense of status. Each states an individual’s name, the span of their life and shows the place where they are buried, nothing more. There is a careful balance between the simple formality of the stones and their configuration, and the curving pathways and placing of trees and bushes.

In the British Cemetery, the design of tombstones varies greatly. Many of the stones are small and simple; the majority are carved and decorated; some are very large, some mausoleums. Their layout is more haphazard than Temple Hill’s. Some texts are very short, others long and complex, often almost a brief biography of an individual’s achievements and excellence. These are public statements which emphasise someone’s status.

Both of these places give dignity to the people who have been buried. Both differ from the standardised layout of most cemeteries, where graves are in ranks, paths are straight and at right angles to each other, and where trees have only a token presence with no rationale about where they have been sited. There is little sense of the importance of sound and texture of pathways - most are tarmac.

In Temple Hill and Corfu, the first sight of the pathways draws a visitor into the ground. This experience combines with sound and texture. The layout of trees and plants builds up a peaceable experience. It is impossible to see the whole of either place from a single viewpoint. Each viewpoint suggests another, but only suggests. In each place, the relationship between sound and memory, memorialising the dead and living experience is powerful.

Too often, a cemetery is a place where the dead are buried and left. In Corfu and Temple Hill, no-one simply walks in and out quickly. These burial grounds are important for the living. People walk very slowly, absorbing a complex and calming experience.

Seán McCrum,

December 2020

Temple Hill Burial Ground is in Blackrock, Co. Dublin. Its main gate is on Temple Hill. Each week in Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown’s Summer of Heritage, there is a tour of the Burial Ground. Please go to their site, events.dircoco, to find out dates and times.

The British Cemetery is in Kolokotroni 22, Corfu 49100, Greece. It is open daily.

Black and white photographs of the British Cemetery, Corfu by Seán McCrum; colour photograph of Temple Hill Burial Ground, Blackrock, County Dublin by Doreen Kennedy.

You may like to hear two sound recordings from Temple Hill Burial Ground by clicking on the

links below. We hope you will enjoy listening:

Sound #00093 Storm Emma nwar Meeting House, Temple Hill Burial Ground, Blackrock

Sound #00091 A quiet summer afternoon at Temple Hill Burial Ground, Blackrock

21/08/2020

Pigeon

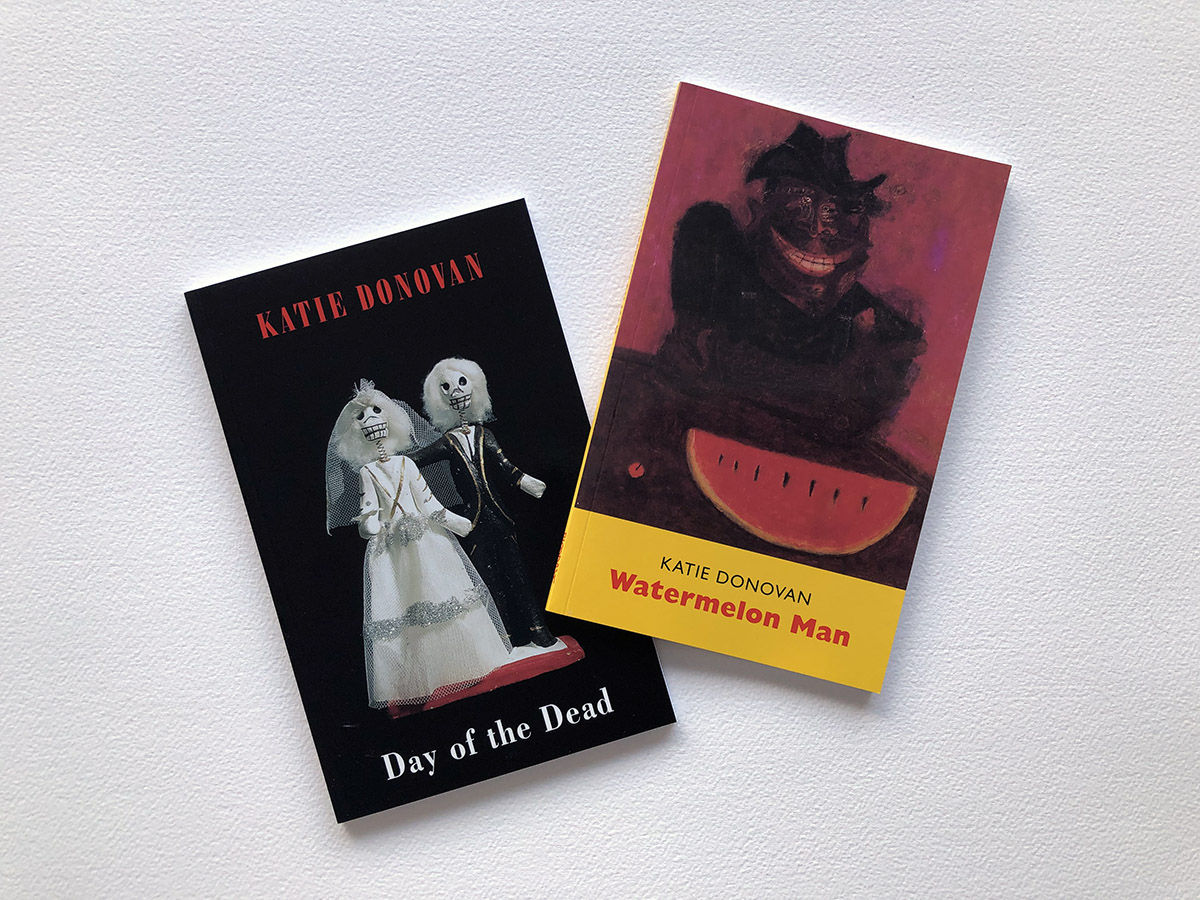

By Katie Donovan

* * *

The afternoon

is ringed

with a pigeon’s croon:

“Go home - now, Katie;

go home.”

Go home where?

I had severed parents,

one remaining on the farm;

the other moving on.

My brother and I

took the train,

chuntering from Dun Laoghaire

down the Wexford line

each weekend.

We’d brace ourselves

for the unsettling;

wary in transit:

me, the elder,

bristling to defend him.

On the farm,

pigeons roosted

in sheds brim with hay;

rooks cawed

in enormous trees;

sheep bleated

to frisking lambs.

Sounds so different

from the ice-cream van,

its tinny tunes echoing

through suburban lanes;

from the boats that clinked

along the seafront;

the foghorns.

I stand in the quarry

where the stone

to build the harbour piers

was hewn.

In the vast hollow

of remaining rock,

the pigeon makes

its call:

a familiar song

of displacement;

exile -

but one

that built me.

Katie Donovan c 2020

You might also like to hear this sound recording by clicking below:

Sound #00106 Pigeons and other nearby birds, Sallynoggin

03/03/2019

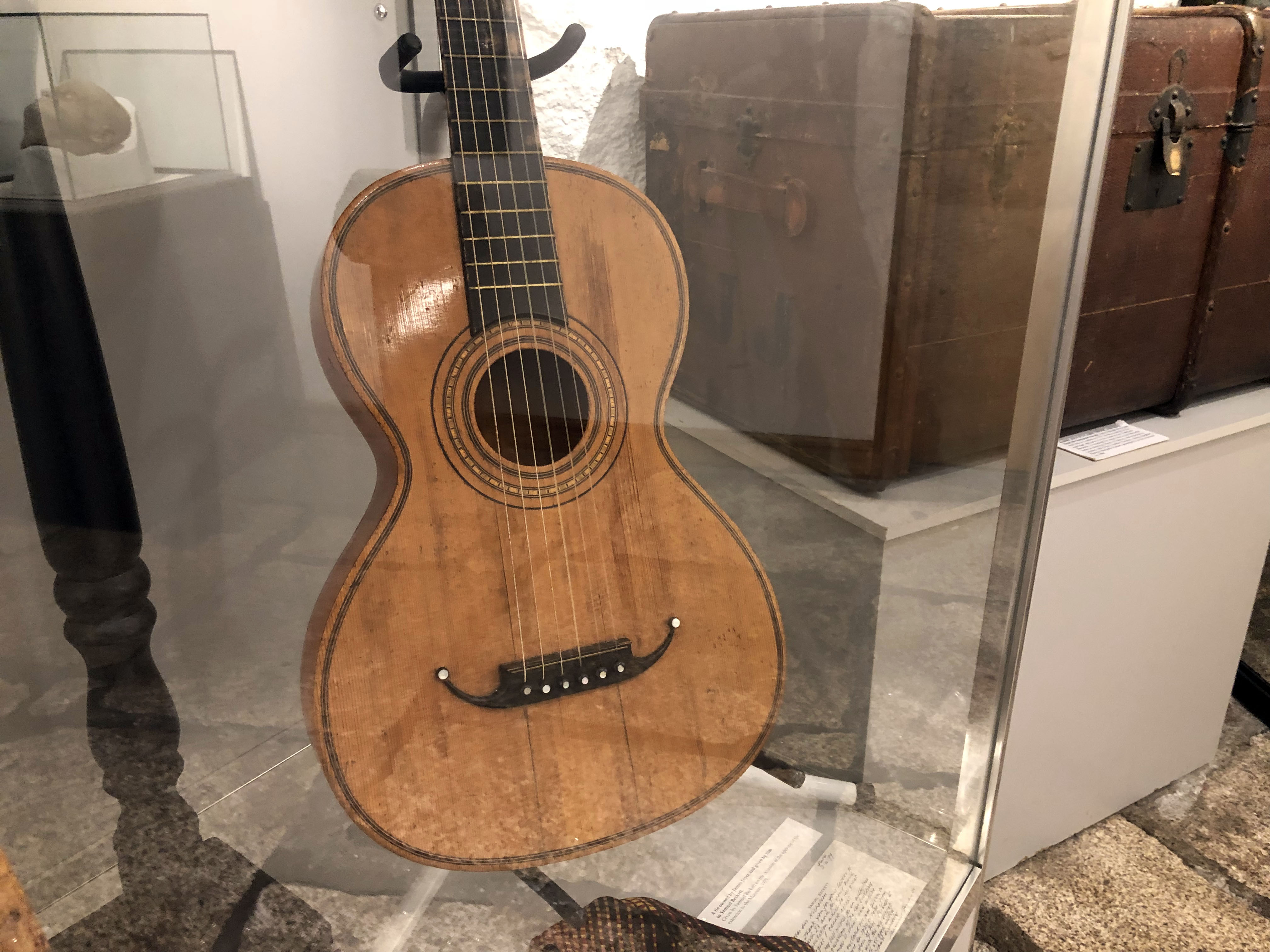

James Joyce's Guitar

By Paddy Sammon

"The guitar that fellow played was so expressive"

- Molly Bloom, in her long soliloquy at the end of Ulysses

***

James Joyce, born in the Dublin suburb of Rathgar in 1882, left Ireland in October 1904, not long after the brief few days he stayed in the tower now named after him. He lived with Nora Barnacle and their two children in Trieste; in Paris, where his most famous work, the novel Ulysses, was published in 1922; and in Zurich, where he died in 1941. The James Joyce Tower in Sandycove, overlooking a headland six miles southeast of Dublin, is the place of pilgrimage for Joyceans from all over the world, especially around 16 June, the fictional Bloomsday, the anniversary of the day in 1904 when all of the action in Ulysses takes place. The opening scene in Ulysses is enacted on the roof of this tower.

Whether you are on a visit to the tower itself, or on a virtual tour on the Sound Map site, the best way to get your Joycean bearings immediately is – counter-intuitively, without stopping even to look at the famous guitar or the other exhibits – to go up from the ground level to the roof, up the tiny spiral staircase, and then to descend at your leisure.

Once you are on the roof, you will discover why no two visits here are ever the same – the Irish weather and the state of the tides see to that. Appropriately for the location of the opening scene of a novel based on Homer's Odyssey, written by an author steeped in the ideas of Aristotle, two Greek-derived words best describe your visit: panorama and synaesthesia. You are now in one of the "Greekest" places outside Greece: Joyce has Buck Mulligan call the tower the omphalos, or belly-button. It has one of the best panoramas in the Dublin area, with the Kish lighthouse out to sea and, landwards, the granite quarries at Dalkey. This location's synaesthetic effects also encompass the sound of the wind howling around you; the shrieks of the seabirds (or are they harpies?) diving into the scrotumtightening sea; the smell of seaweed; the taste of salt in the air; the rough feel of the granite parapet.

The granite walls of the Martello tower are eight feet thick: twenty-six of these towers were built around Dublin Bay, so as to withstand the rigours of a possible French invasion in Napoleonic times. They were constructed in record time under the terms of the Defence Act of 1804, exactly a century before the fictional date of the action in Ulysses.

After the brief descriptive opening, the first words voiced in Ulysses are not spoken, but intoned: Introibo ad altare Dei. These are the introductory words of the Latin Mass, and are taken from the Latin Vulgate translation of the psalms: Et introibo ad altare Dei ad Deum qui laetificat iuventutem meam confitebor tibi in cithara Deus Deus meus: "I shall go up to the altar of God, the God who gladdens my youth, I shall praise you, God, my God, on the cithara". This is from the Psalms (a Greek word meaning instrumental music), which were sung, rather than spoken. In English translations, the word cithara is usually translated as harp or lyre. It is the word from which derive the Spanish word guitarra, and hence English guitar.

You now come down again via the spiral stairs to the main living-room: this circular room works like an echo chamber, not unlike the sound box of a guitar. But you are now inside what was, in its day, a very sophisticated military installation. You can imagine that you are one of the Greek soldiers transported into Troy in the belly of the Trojan horse. It was the crafty Odysseus (whom the Roman poet Virgil called Ulysses, the Latin version of his name, hence the title of Joyce's book) who came up with the ingenious idea of making the wooden horse and of inveigling the Trojans to bring it inside the walls of Troy.

Hearing Joyce's own guitar being played inside these walls accompanied by a tenor voice such as Joyce himself had, is a wonderful reminder of how important music was to Joyce and to his works. Just as Homer was said to be blind, Joyce suffered all his life from poor eyesight, and the sounds of his words were perhaps even more important to him than how they looked on the page.

Come down once again via the spiral stairs to the internal room, formerly used as the store-room for explosives. There in the showcase, beside his walking stick, is Joyce's guitar, generously donated to the tower in 1966 by his friend Paul Ruggiero. The guitar, which we know was owned and played by Joyce, dates from about 1830. Mostly people are aware of it from a photograph taken in 1915 by Joyce's friend Ottocaro Weiss in Zurich (See: https://joycefoundation.osu.edu/people/joyce-5). Joyce gave the instrument to his friend Paul Ruggiero in the late 1930s, and in turn Ruggiero donated it to the Joyce Museum. The guitar, not the work of any great instrument-maker, was a fairly standard instrument of its time. It still shows signs of wear and tear left by Joyce and its previous owners.

For many years Joyce's guitar was also unplayable, until Dr Fran O’Rourke, a professor of philosophy at UCD, who also likes to sing Joycean songs, orchestrated the restoration of the guitar by the English luthier Gary Southwell, using the facilities of the conservation department of the National Museum of Ireland at Collins Barracks. Some of Ireland's most precious possessions have been conserved there, including the bog bodies found in recent decades, and the bog book, known as the Fadden More Psalter, an archaeological find unique in world terms, which contained the Latin text of the psalms. Joyce would surely be skipping in his Swiss grave at the thought of finding the words "Introibo ad altare Dei" (Psalm 42) among the more mangled pieces of the Fadden More Psalter. While the bodies of Clonycavan Man and Old Croghan Man, conserved shortly before the guitar was brought back to life, remain silent, we at last have the chance of hearing the chords which Joyce played to accompany his own singing voice. We are lucky to have a few recordings of James Joyce's voice, reading some of Finnegans Wake in his wonderful Dublin accent, and since 2012 – fifty years after the tower opened – we also have the opportunity to hear his very own guitar.

[Link to "In Old Madrid" , mentioned in the Eumaeus episode of Ulysses:]

You can listen to these Joyce related songs by clicking on the play button. We hope that you will enjoy them.

-

Sound #00086

- Sound Title: The Lass of Aughrim, John Feeley - Joyce’s restored guitar, Fran O’Rourke - vocalist

- Duration: 5:08

- Location: Joyce Tower, Sandycove, Dun Laoghaire

- Date/Time: June 2013

- Author(s): Gary White

-

Sound #00087

- Sound Title: Slán le Máigh, John Feeley - Joyce’s restored guitar, Fran O’Rourke - vocalist

- Duration: 4:35

- Location: Joyce Tower, Sandycove, Dun Laoghaire

- Date/Time: June 2013

- Author(s): Gary White

The above Joyce-related songs feature John Feeley playing Joyce's restored guitar and Fran O'Rourke as vocalist. It is not every guitarist who can manage to play such a venerable instrument: John is one of Ireland's foremost players and teachers of guitar. Together they form an ideal partnership to recreate the atmosphere of Joyce's fine singing voice, of which no recordings exist, combined with the original sound of his guitar.

THE LASS OF AUGHRIM (traditional)

If you be the lass of Aughrim

As I suppose you not to be

Come tell me the last token

That passed between you and me

O Gregory don’t you remember

That night on the hill

When we both met together

Which I am sorry now to tell.

The rain falls on my yellow locks

The dew it wets my skin

My babe lies cold within my arms

Oh Gregory let me in.

Of all the songs that feature in Joyce’s work, ‘The Lass of Aughrim’ has perhaps the greatest resonance. It inspired the atmosphere for his most famous short story 'The Dead', the final story in Dubliners. It evokes in Gretta haunting and remorseful memories of Michael Furey, her youthful sweetheart who sang the song, and whose death was occasioned by their parting. Its performance at the dinner party earlier in the evening anticipates the final poignant scene: ‘The song seemed to be in the old Irish tonality and the singer seemed uncertain both of the words and of his voice. The voice made plaintive by the distance and by the singer’s hoarseness faintly illuminated the cadence of the air with words expressing grief: — O, the rain falls on my heavy locks / And the dew wets my skin, / My babe lies cold…’. Joyce wrote to Nora Barnacle: ‘the tears come into my eyes and my voice trembles with emotion when I sing that lovely air’.

SLÁN LE MÁIGH (traditional)

The second song is a farewell to the river Maigue, which flows mostly through Co. Limerick. The lyrics were written in Irish by Aindrias Mac Craith (c.1709-c.1794), who was jokingly known as 'An Mangaire Súgach', the Merry Pedlar. He was in fact a hedge-school master and had a great facility with words. It was 'drinking deep and beauty wooing' that caused him to have to leave Croom, Co. Limerick, in a hurry. One suggestion is that the parents stopped sending their children to his school, another is that when the local priest got into a dispute with him concerning a girl in his parish, the poet offered to convert to Protestantism, but this was refused by the local parson.

Ó slán is céad ón dtaobh so uaim,

Cois Máigh na gcaor, na gcraobh, na gcruach...

A long farewell I send to thee,

Fair Maigue of corn and fruit and tree...

This is one of the most exquisite songs in Irish: the lyrics are superb and the music is hauntingly memorable. The Irish language (which Joyce did not however know) lends itself very easily to being sung because of its pure vowels. Joyce sang the translated version at the Feis Ceoil in Dublin in 1904, and won the bronze medal in the tenor competition.

Visually, a common image of Joyce is in his later years, wearing John Lennon style glasses and using a magnifying glass: we think of him as dealing in the written word. Equally valid is an aural Joyce: to judge from his writings, his head was filled with music and song. There are hundreds of references to the words of songs throughout his works, and in another incarnation the Joyce we think of as a writer could have ended up as a singer.

Paddy Sammon, April 2019

***

The songs 'Lass of Aughrim' and 'Slán le Máigh' were recorded by Gary White during an evening of poetry and song performed by poet Paul Muldoon, guitarist John Feeley, and singer Fran O'Rourke in the Joyce Tower in June 2013. 'Lass of Aughrim' is central to Joyce's most famous short story "The Dead". Joyce adapted lines from the English translation of "Slán le Máigh" for use in Finnegans Wake. Fran O'Rourke's singing of "Lass of Aughrim" is accompanied by John Feeley on the guitar originally owned by James Joyce which is displayed in the Tower. Fran O'Rourke and John Feeley sponsored the restoration of the instrument in 2012, with generous donations from Paul Muldoon, Friends of the Joyce Tower, and Peter Caviston.

Fran O’Rourke, April 2019

Our sincere thanks to Paddy Sammon, Fran O'Rourke, John Feeley, Gary White, Robert Nicholson and all at the Joyce Tower, Dun Laoghaire

Picture credits:

First image: James Joyce’s guitar on public display, at the Joyce Tower, Sandycove, Dun Laoghaire.

Second image: John Feeley (holding Joyce’s guitar) and Fran O’Rourke at the Joyce Tower, Sandycove, Dun Laoghaire.

November 2017

At Land

By Helen Frosi

A STARTING POINT

[…] the world reduced to sound (1)

I am sitting in my study, around me are stacks of unread books, collections of dried leaves and other natural ephemera, half-obscured Polaroids of places I’ve hazy memories of visiting, age-curled postcards and jars of marbles, tiddlywinks, walnut shells. In front of me my laptop. I weave through images and texts, strings of thought and the senses that guide me down through time and across experience. I look around my study, see what is in front of me, all jumbled stories. I put on my headphones, begin to listen to audio collected from a land I’ve never visited. My eyes are here, but my ears are lost in a world of mystery miles away.

THINGS TO NOTE

I. It is through other ears that I hear.

II. Here, I am around 365 miles from home.

III. I move across time as if it was a road.

VI. The map is not the territory.

AURAL JUXTAPOSITION

The scientific ear

The poetic ear

HEAR HERE

I am. I am ear. An ear to the ground they say. When I’m positioned horizontally I cannot see, but who needs sight anyway when you have hearing? That sense that is all vibration, all spirituality; all universe at beginning and end. And, of course, I have an ear for sound making especially a good old racket – the stuff we loath on a weekday night (when we have work the following morning). Hilarious really when it all boils down to the furriness of my coat lining, and how much it likes to party. Well, I can tell you, I slammed my bones the other night dancing to the roar of some Heavy Jazz and now all I hear is the echo of my own voice – a constant and persistent nag that crackles and rings like a TV, channels out of tune.

~eeeeEeeeeeeEEEeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeEEeEeeeeeeeeeEeeeeeee

EEeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeEeeeeeeeEeeeeeeeeeeeeEeeeeeeeeeeee

eeeeeeeeEeeeeeEEEeEEEEeeeeeeeeeeEEeeee

eeEEEeeeeeeeeeEEEeeeeeeeeeEEeeeeeeEeeeeeeEEe

EEEeeeeeeeeeeeeEEeeeeEeeeeeEeeeee

EEEEeeeeeeeeEEEeeeeeee~

AMPLIFICATION

I AM NOT SHOUTING

I AM SIMPLY LISTENING TO SOMETHING

THAT IS RATHER LOUD!

Be not afeard. The isle is full of noises, Sounds, and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not. Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments Will hum about mine ears, and sometime voices (2)

SOUND = MUSIC.

DISCUSS...

#00040

Incoming Tide, Bullock Harbour, Dalkey

-

Sound #00040

- Sound Title: Incoming Tide, Bullock Harbour, Dalkey

[A gentle lapping:

lulling the ear to an horizon of vibration.]

[A stone topples, and lands on a flat surface,

its uneven surface rocks as a boat’s keel during inclement weather.]

AURAL JUXTAPOSITION

The filmic ear

The dreaming ear

HEAR HERE

I am an ear with fleshy lobes – wise they say. Some days I’m adorned and praised whilst others, I’m tortured with noise or my flesh pierced! I am the bringer of balance, which most of us don’t care for – we prefer to spin in the opposite direction, send the brain to places it can never quite grasp. Giddy it into hallucinations – what was that? Did you hear that too? Say again? But I work with the flirtatious. That beguiling thing that will not stop for man or beast; nor the brightest stars of the Heavens. But maybe one day, there will be technology enough to capture it. Capture sound. But as sound and not as audio; live sound that somehow remains live. Not disembodied voice perfect in its looping. Play it again so we might learn a thing; so we might heed something that we first missed.

A QUESTION

What is resonance; can it be recorded?

A THEORY

“The Stone Tape theory is the speculation that ghosts and hauntings are analogous to tape recording, and that electrical mental impressions released during emotional or traumatic events can somehow be "stored" in moist rocks and other items and "replayed" under certain conditions. The idea was first proposed by British archaeologist turned parapsychologist Thomas Charles Lethbridge in 1961. Lethbridge believed that ghosts were not spirits of the deceased, but simply non-interactive recordings similar to a movie.” (3)

#00051

Church Bells, Seagulls and Ambience

-

Sound #00051

- Sound Title: Church Bells, Seagulls and Ambience

[Moving from within to without;

Listening through walls, through time.]

A QUESTION

Can one invent new ways of perceiving place, or does place reinvent itself?

TWO SOUNDS FOR THE EYES

-

Sound #00052

- Sound Title: The water feature at DLR Lexicon

-

Sound #00031

- Sound Title: Sandycove, Garden near Joyce Tower

INSTRUCTION

A different place; a different time. Overlay audio from disparate origins to create new ways of listening through temporal layers, contrasting resonances, miss-hearings and sonic muddling.

#00040 | #00031

Incoming Tide, Bullock Harbour, Dalkey

Sandycove, Garden near Joyce Tower

ACTIONS FOR A SOUND MAP

Listen to a recording as if you are the recordist.

Listen to the recording as if you know the place.

Listen to the place as if you are a stranger.

Listen to only that which is other.

Listen for the familiar.

Listen with no prior knowledge.

Listen to movement and to stillness.

Listen to the space.

Listen through.

Listening to the silence of a place.

All materials are alive –

at least in the sense they

have potential to make sound.(4)

POINTS OF LISTENING

Point of view of the recordist

o

o

Point of view of the recorded subject

(e.g. person)

o

Point of view of the object

(e.g. sky, stone)*

*example:

Field Recording #00033

Autumn Leaves, Granitefield

-

Sound #00033

- Sound Title: Autumn Leaves, Granitefield

AURAL JUXTAPOSITION

Think yourself the still ear (listen in stillness)

Think yourself the roving ear (listen with movement)

EXTENSIONS

[[Describing the same place on another day

[[Describing the same place through a variety of mouths

[[Describing sound via different vantages

[[Describing sound via many sensitivities

[[Describing sound via other senses

SITUATION

21 April 2013, 3:03pm.

A local man walks to the cove from his house. It is a weekly ritual that has taken hold of him since he was a small boy, a time enamoured by marine rainbows and other stories of the sea passed down from old to young.

He observes the mid-blue of the April sky and turns up his collar at the nip of spring’s gentle breeze. The sun’s light on his face tingles like seaweed fronds drying on wind-dried stones.

He is prepared. He has his best leather boots on, bought for the clipped sound they make on stone cobbles. Promenading close by the beach he breaths in the briny air, allowing the effervescent sound of waves to lure him toward the broad expanse of blue: the sea, and the sky: both brother veils.

Standing for what seems an eternity, sounds flow around him as if time was getting old. For a moment he is distracted by passers-by, their own voices alien and yet speaking of the things all humans do.

-

Sound #00001

- Sound Title: Sandycove Beach

NOTES ON A SONIC MEMORY

It is a Sunday afternoon and I have with me nothing but the memory of sound. Sounds from a place I have not yet visited; sounds that inspire my imagination to the notion of translation.

I am thinking and I am writing and I am allowing the memory of the sound to take my imagination to a place of pen and ink. A line forms. Many lines form. Clots of paper layer with tendrils of drying ink. My fingers hold the pen; it takes flight as the memory of sound becomes pure imagination. The action of pen to page transfers ink across the side of my hand. Stark lines become oceanic smudges: an ink that at first flows freely and after a time is light and faint as clouds on a winter morning. High crystals about to explode.

I translate and read and read and translate until the lines and blotches become the spaces between sound in movement and the stillness of silence. I hatch a plan for tomorrow. An action to open my drawing on sound:

LISTEN NOT WITH THE EARS**

A QUESTION

Might what is left unseen/heard be the key to our understanding of our surroundings?

AN ANSWER

[Standing still to mimic

the silence of this gentle night.]

-

Sound #00028

- Sound Title: Night Recording at Dillon's Park, Dalkey

**An end point

___________________________________

(1) Anne Tannam, [excerpt] The World Reduced to Sound,

taken from Take This Life (WordOnTheStreet 2011)

(2) William Shakespeare, [excerpt] The Tempest; Act 3, Scene 2; Page 7.

(3) Wikipedia entry: Stone Tape – accessed 08 February 2016, 13:00.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stone_Tape

(4) Pete Mullineaux, [excerpt] A Slow Start to the Set, in Session

At Land

A response to A Sound Map of Dun Laoghaire

Helen Frosi

Tottenham and Stratford, November 2017

21 Dec 2016

Tribute to a Sound

By Simone Corr

In 2011 without fanfare, the foghorn was decommissioned from our coast line. A single Notice to Mariners was issued by the Commissioners of Irish Lights and it became so. Living on an island makes mariners of us all, so weather is never far from our consciousness. Island nations and coastal regions are more susceptible to fog. The biggest influence on Ireland's climate of course is the Atlantic Ocean, so the sea area and shipping forecasts subliminally enter our lives.

While Ireland, its western seaboard or stretches of the M50 may seem the foggiest places on the planet, they are not. The aptly named Cape Disappointment, (Washington State) and Grand Banks, (islands off Newfoundland) hold records in the extremes.

Meteorological Services measure visibility as: good, moderate, poor and fog. Where fog has a visibility of less than 1 km.

What is harder to measure are the innumerable references for fog when used as descriptor, metaphor, catchphrase, symbol, theme or motif. Fog within film and literature is used to great effect. Often indicating something menacing, making that which is visible, invisible. Robert Louis Stevenson, Bram Stoker and Dickens all used ‘foggyscapes’ to set the atmosphere.

"Before Turner there was no fog in London" writes Oscar Wilde in the Decay of Lying "The extraordinary change that has taken place in the climate of London during the last ten years is entirely due to a particular school of Art. At present people see fogs, not because they are fogs, but because poets and painters have taught them the mysterious loveliness of such effects. There may have been fogs for centuries in London. I dare say there were. But no one saw them, and so we know nothing about them. They did not exist until Art had invented them. Now, it must be admitted, fogs are carried to excess."

The cloaking fog of a winter’s evening sometimes makes noise sound hollow or distorts the distance from its source, car headlamps can cast shadows in 3-dimensions, typically through structures such as pylons or bare tree branches. During foggy conditions, sounds from the city will differ from sounds at sea, the foghorn as example is an audible warning to ships and small craft. In the earlier years cannons were used, explosive charges, bells and whistles, but these methods required manual resources. In the 20th century foghorns became electrified and automated. Now with navigational aids so advanced, sonar, GPS and recon are the eyes and ears of the modern seafarer. Commercial ships are still required to use foghorns, but they will no longer sound from our shores. Tribute to a Sound commemorates the decommissioning of the foghorn.

Simone Corr, Dec 2016.

Watch the short film Tribute to a Sound by clicking the play button below:

20/06/2016

Willie Brady and his musical legacy

By Jay Roche

Life in post war Ireland in the 1940s and 1950s was tough going and light on entertainment. People worked hard for little, and any kind of recreation had to be done on a shoestring. Television hadn’t taken a hold on family life and the cinema, although popular, was at the very most a weekend treat. Radio was ubiquitous with a wireless in most homes, however people wanted to see as much as hear those that were entertaining them. It was therefore not unusual during this period for folks to make their own entertainment either as a family or on a local community basis. The family piano or the community hall were the gathering points for those looking to wile away a summer afternoon or a winter evening.

Dún Laoghaire was no different to the rest of the country in this respect and although it was probably more metropolitan than other parts of Ireland there was still a demand for a good knees up or a sing song. One advantage this parish had was of course it’s proximity to Dublin city, its port and its own harbour which brought in influences from abroad quicker than might have been the case in more rural parts of the country.

Let’s not also forget the beginnings of the popular music revolution that started in the U.S. and spread to Europe was at this time bringing recorded music into the homes of many via the gramophone and wireless. The people of post war Ireland were becoming familiar not only with Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby but also the revolutionary rock and roll records of Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry. Recorded music was at the beginning of a boom but far from stifling live acts it helped to inspire and bolster an up-swing in young people keen to follow in the steps of their idols. It also introduced a new range of songs emanating from the Brill building in New York or Tin Pan Alley in London.

It was into this world that the Brady family, who hailed from Rosary Gardens, off Library Road, brought their many talents. The Brady/Taylor’s were a gifted family of musicians and performers who had entertained their neighbours going back to Victorian times and who were typical of other families throughout Ireland who brought their talents to the local community - often by recreating the songs and routines of the worlds top musical acts. In the case of the Bradys this would take the form of seasonal pantomimes and ‘Musical Reviews’ held in the local hospital, convent hall or on occasion in the Pavilion theatre. These shows were often recreations of well known scenes taken from the films of Walt Disney or renditions of songs from the great hollywood musicals by Rogers and Hammerstein. Tunes such as ‘You’ll never Walk Alone’ or ‘Moon River’ by Henry Mancini were met with equal enthusiasm to the more traditional Irish ballads and folk songs. Popular versions of ‘The Foggy Dew’ and ‘The Wind that Shakes the Barley’ were common choices. Throughout the 1940’s, 50’s and 60’s the growing members of the Brady family from grandparents down to grandchildren offered seasonal entertainment in various venues throughout the borough.

It is no surprise that out of this talented group would come someone who would seek to pursue entertainment as a profession. That person was Willie Brady who went on to start a recording career in the late 1950’s. Willie was both a talented singer, musician and entertainer with a sharp wit and a flair for comedy. He took after his mother Nan Brady (nee Taylor) in being a natural musician with a fine singing voice. His musical repertoire was gleaned not only from the popular songs of the day, sung by Sinatra, Crosby and Martin but also the more traditional music hall favourites and the folk songs of Ireland and Britain. One particular favourite was ‘The Patriot Game’ written by Dominic Behan, of which you can hear a recording below. Willie would tour Ireland playing everywhere from the Olympia theatre in Dublin to the community halls of villages around the country. He was known abroad and played New York and London and would have been very popular amongst the Irish communities in those cities.

Willie was also well acquainted with the some of the bright lights of Irish entertainment and would have played many a variety show often joining with comedian Hal Roach to form a duo for shows in the Gaiety and other theatres around the country. Willie and Hal became well known on radio and travelled throughout Ireland and the UK with their mix of light entertainment and comedy. Another person Willie knew from his boyhood was Dún Laoghaire native Ronnie Drew who grew up in Monkstown Farm and would have known the Brady’s as neighbours. Willie gave Ronnie his first banjo lessons and Ronnie would have learned songs from the Brady’s as a young man. Years later Ronnie often payed tribute to Willie on many occasions and shared songs that Willie had taught him. Tragically Willie died in 1968 of a short illness whilst still in his prime at the young age of 38.

You can hear Willie sing ‘The Patriot Game’ by clicking on the audio player below.

-

Sound #00057

- Sound Title: Willie Brady ‘The Patriot Games’

- Duration: 4:00

- Location: Cross Avenue

- Date/Time: 1960s

- Author(s): Willie Brady

There was still plenty of talent left in the wider Brady family and Anne Byrne, Willie’s niece was already making a name for herself in the Irish music scene. Anne was the eldest of the Byrne family (her mother was Willy’s sister, Brigid ‘Queenie’ Brady) and she grew up on Tivoli Terrace North. The Byrne family were all wonderful singers and Anne in particular had a sweet soprano voice. She was the winner of many Fheis Ceoil in her teens and by 19 was already a recording artist. As already mentioned, Anne would have been familiar to the citizens of Dun Laoghaire from the various performances put on in St. Michaels hospital and the Dominican Convent by the Brady and Byrne clans during the 40’s and 50’s. Anne, like her Uncle Willie, would have had a repertoire of traditional Irish Ballads and folk songs that were now gaining popularity across the globe due to the folk revival in the US and also in the UK.

Anne found herself on the crest of a wave of folk revivalism and she was soon a regular on TV and Radio and a performer of concerts around Ireland and Britain. She first formed a duo with singer Jesse Owens and they released a number of albums together, his rich tenor complementing her high soprano. Anne appeared on numerous radio and television programs at the time and her and Jesses’ albums sold well both here and abroad.

Anne had already met her future husband Patrick Roche in 1965 and it was Patrick’s interest in the contemporary folk scene that led Anne to include more recent songwriters. She began to cover songs by writers like Gordon Lightfoot and Eric Anderson along with obvious the hits of Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell. Her interest in the American folk scene led to comparisons in particular with Joan Baez and indeed both voices are similar, however Annes’ Irish lilt and intonation added an extra charm to her renditions. Anne’s talents were noted by Irish songwriters and her biggest hit was written for her by Irish songwriter Gordon Smith who penned the song ‘Come by the Hills’ especially to suit her voice.

From around 1968 to 1975 Anne experienced the height of her success with 4 solo albums released between these years. Other hits such as Avondale (written about the Irish politician Charles Stuart Parnell) and Bunclody continued to increase her fan base. In 1969 she travelled to New York where she took up a residency in the famous Irish Pavilion singing alongside the Clancy brothers and Judy Collins. She also played the Philadelphia folk festival sharing a stage with the likes of Leonard Cohen and Gordon Lightfoot. She would continue to return to the states over the next few years for tours around the east coast where her Irish American fan-base was most strong.

Anne continued to record and perform in Ireland up until the late 70’s. However, the demands of motherhood and a change in musical tastes led to her becoming less and less involved in the music scene. In many ways the stresses and strains of performing were unsuited to her and she retired from live performance in the early 80s.

Although during the busiest years of her career she lived away from the borough of Dun Laoghaire she finally returned to live there in the mid 80’s and there was a continuation of the sing alongs and get togethers, now focused in the Byrne homestead on Tivoli Terrace. This enduring musical legacy has already rubbed off on a new generation with Anne’s nephews John Lambert (as Chequerboard) and Rhob Cunningham both recording and releasing their their own music over the past few years.

Jay Roche, June 2016

With thanks to Shane Brady, Anne Byrne and Patrick Roche

You can hear Anne talk about performing her music in Dún Laoghaire and other fond recollections by clicking on the audio player below. We are very pleased to have a recent recording from July 2015 of Anne singing ‘Come by the hills’ accompanied by Patrick Roche on guitar.

-

Sound #00058

- Sound Title: Anne Byrne & Patrick Roche talk about performing music in Dún Laoghaire

- Duration: 5:41

- Location: Cross Avenue

- Date/Time: July 2015

- Equipment: Rode NT4+SD702

- Weather: Indoors

- Description: Anne Byrne and Patrick Roche recollect the days when they performed their music in Dún Laoghaire. Anne also talks about Wille Brady and some other famous locals from the borough. Anne, accompanied by Patrick Roche sings ‘Come by the hills’ one of her best known songs.

- Author(s): Anthony Kelly

Picture credits:

Top: Willie Brady by unknown photographer.

Group image: Christmas Pantomime circa. 1950s, Dominican Convent, Dun Laoghaire. Third from left Rosaleen Brady, Edmund Byrne, Patsy Brady, Queenie Byrne (nee Brady). Anne Byrne is third from the right. Photographer unknown.

Below: Jay Roche by Ciara Brehony.

14/09/2015

Transplanted Nostalgia

By EL Putnam

Artists engage with the world in a way that taps into sensory experiences that may otherwise be taken for granted. The artist lets the senses guide you—a mode of navigation not bound by reason. When an artist maps a site, acoustically in this instance, sound becomes the means of communicating the essence of a place. A sonic ambiance is cultivated as the artist collects snippets of daily life, tracing his or her presence cartographically. Sharing a fragmented soundscape in a geographic form allows others to not only gain perception into the artist’s journey, it situates these experiences in a real place. As such, A Soundmap of Dún Laogharie presents navigable sonic insight into this artistic portrait of a borough. Throughout the project, Stalling and Kelly have taken on the role of composers in this orchestrated soundscape by cultivating an aesthetic experience of this distinctive borough.

As a relative new-comer to Ireland, I appreciate how this sound map allows me to become more familiar with Dún Laoghaire (I have to check the spelling every time I type those words). David Stalling’s recording from the playground in the Belarmine Estate above (Sound #00006) carries notes of familiarity, evoking a nostalgia for my own childhood of many summer days spent playing nearing my home in the cul-de-sac of Ruxton Road. The sound of birds chattering mixed with children playing and echoes of traffic noises fill my ears. The murmur of parents slips in and out of the background. I close my eyes and let the sounds encircle me. An adult coughs—I turn slightly to the left. I hear a ball pounding on the pavement. A young child giggles. “Kick it to me, please.” A bicycle whizzes by. The more I listen to this pleasant scene of play, leisure, and social exchange, with its blend of natural and urban noises, the more immersed I become in this slice of daily life. I go so far as to imagine the warmth of sun light on my skin.

I then turn to Sound #00033, “Autumn Leaves, Granitefield,” recorded by Anthony Kelly along Rochestown Avenue. I can hear his footsteps crunch along the dry leaves that amassed along the route. Cars drone in the background as Kelly strolls along. The crunching transitions from measured steps to boisterous noise, almost like the static of a radio stuck between stations. A twig snaps. I can imagine Kelly pushing his way through a collected pile of leaves—another sound that I can trace to my own childhood.

Even though the artists provide an annotated map for me to follow, there is no directive on how I am to engage with this map. The sounds are numbered, though I do not need to follow them in order. I can hop from location to location, or I scan through a list and explore those I find provocative. I let these carry me back to map, where I continue to jump from link to link. How I experience Dún Laoghaire depends on how I decide to navigate. The artists have set the parameters, but I create the new world depending on how I piece my experience together. As such, A Soundmap of Dún Laogharie is performative—constitutive—as its contributors collect sonic traces of a place, and offering a non-linear path for the user to navigate. Treating mapping as performative means that it is treated as generative, rather than reflective.

While my experience of this borough are relatively limited, listening to this diverse collection of sounds provides me with a sense of familiarity of the place. Some sounds, like Stalling’s recording of the playground, offer an overview of the scene, like an establishing shot. I feel like a fly on the wall, just taking in the surrounding environment. With other sounds, like “Autumn Leaves,” I am placed in the midst of action. Throughout these recordings, I am granted with a keyhole glimpse into the daily life of this region, as in Kelly’s recording of young people swimming in Colimore harbour (Sound #00038). The lapping of waves dominate this track, making me feel as if I am swimming through the bay itself. I hear children joyfully splashing, chatting back and forth with voices heavy with breath due to the exertion of energy. Seagulls proclaim their presence. A woman and child are in the midst of a swimming lesson. Mother and son? The heavy splashing of an inexperienced swimmer, learning to control his arms and legs break through every now and again. “I can’t.” “You’re lazy.” He swims on. “Well done.” The intimacy of this experience is engrossing.

What I find distinctive about A Soundmap Dún Laoghaire when compared to similar, web based audio-cartographic projects, is the care that its contributors put into the act of recording. Sound #00043, “Seagulls and Pigeons,” presents a verbal exchange between Stalling and an elderly woman. She has stumbled upon him as he is recording and begins to discuss the particularities bird plumage colours: “There are lots of white feathers with the pigeons and I think they have a romance with the seagulls. Don’t you? [Laugh]. I hope they do!” Her excitement over the variety of avian colourings keep her from even finishing her sentences as she leaps at the chance to describe the features of different birds. Traffic sounds and the beeps of a crosswalk fill the background of this exchange between Stalling and the woman. The conversation is quirky, imaginative, but also grounded in particular experiences.

Mapping as an artistic practice is not novel. It has been documented throughout the twentieth century and earlier, and is a process utilised by Surrealists, Situationists, Fluxus artists, Pop artists, and Dada. The latest advances in digital technology and locative media in the production and uptake of cartography has informed how artists engage with geographies. Digital iterations continue this legacy, while also facilitating the process. As annotated digital maps are becoming more and more popular, a significant aspect of A Soundmap of Dún Laoghaire is the continued emphasis on face-to-face exchanges in the production of recordings. At the moment, Kelly and Stalling have been working with guest recordists who express an explicit interest in participating in this project so they may build a relationship with it, developing an investment in its outcome. This emphasis on non-digital, person-to-person engagement is notable in relation to the digital outcome of the project, since it explicitly merges this platform with physical human relations. At the same time, these interactions also slows down the production of the work, which can be considered a benefit. When it comes to the internet, artists may get caught up on the pressure of producing quickly in order to stay relevant, which inevitably speeds up the process of creation. Speed minimises the space of creative reflection as works can be uploaded for public consumption without a second thought. There are consequences associated with this process. For example, work produced in digital haste may not be thought out well, can be presented in unfinished forms, or is of poor quality. Once a work is placed on the internet, it escapes the artist’s control (though such can be said for any work that leaves the studio). However, the scope of influence that the internet encompasses far surpasses that of a physical object placed in a gallery; it can be accessed at the click of a button by anyone with appropriate digital access. While the method of production is place-based, the final product is not. Thus, slowing down this process and taking extra care in the production of these recordings, which includes engagement with the recordists themselves, offers room to breathe.

As an outsider, there are certain particularities of Dún Laoghaire that will remain foreign to me. These include cultural quirks that despite my best efforts, I may never acclimate to. However, the human relations and everyday actions that make up A Soundmap of Dún Laoghaire offer me a sense of transplanted nostalgia. I am able to connect these sounds with my own memories, transcending impercetible boundaries as I feel a little bit more at home in this adopted land.

21/04/2015

Sound Surprises

By La Cosa Preziosa

It’s a little too early on a weekend morning as I hurry towards the Luas in Windy Arbour. I walk this road all the time, but never this early. The pale grey crescent of pebbledash, usually lively with lights and families going about their business, is lying still and is barely twitching out of its sleep. Because I am alone and I am rushing, I startle as a sudden metallic clicking of heels rises up behind me. I turn around but there’s nobody there. I stop. No sound. No sound other than my own, slightly anxious breathing. Then I clock the sharp architecture of the street corner: the sound of my own steps had ricochet off the walls, as if off a snooker table.

I always enjoy emerging from the Dart stop in Dún Laoghaire, meeting the opposing clangs of steel and traffic. Making the transition from the enclosure of the train carriage, seeing the sea appear behind the glass, I am never quite prepared for the noise. Somehow a train window implies an expectation for everything to be muffled.

The buses at the terminal are exhaling in puffs, all lined up liked bored schoolchildren. The new Library juts out in the distance, and I follow its contours as I make my way down towards the pier. When I get there, the gulls are in the process of losing a screaming match with a roaring mass of grey. Against all this monochrome, the cliff side is as green and as vibrant as ever.

Anthony says: ‘Taking a walk on the West Pier, near the entrance of the pier I can be quite alert to the many busy sounds associated with our town: for example the trains, cars and people at work. But the further I travel down the pier, the more I tune to the harbour and it’s specific and bracing soundscape. Venturing onwards I find that I am leaving the sounds of the town behind: a unique and pronounced sensation of moving ‘outwards’ from the land, accompanied by differing sounds from the sea, now on both sides of the walkway. And when I get to the first turn, I can really become aware of that.’

Today there is no clicking. My steps are slow and deliberate. It’s cold, yet I am wishing this rare moment of quiet reflection could go on indefinitely.

The Victorian shelter and its little brother the bandstand sparkle in the intermitting sunshine, welcoming through a steady trickle of families, of children, of pets. All of us here to walk a topography we know well, perhaps even take for granted, but one that keeps us coming back.

I go on to wonder how and if at all the sounds of this location - flexible, shifting actors in this geographic and weather-sensitive play - register in the conscious experience of the people here today. I can only smile to myself as my thinking gets rudely interrupted by a honk from a distant ferry, waving its deep bass goodbye out of the harbor. There’s my answer.

With A Sound Map of Dún Laoghaire, Anthony Kelly and David Stalling are undertaking a project that – alongside its primary educational, archival and artistic goals – will help its users rediscover with this particular aspect of auditory experience.

The invitation is out to the people who are here today – the elderly gentleman examining the sundial, the boyfriend and girlfriend having their ice cream, the little girl pointing at a little blue boat - to consider the unheard, and to get excited about it. And, maybe, to begin on a process of a collaborative auditory awakening that will in turn inspire to further admire, highlight and preserve the sounds of this location.

Without realising I have come to the end of the pier. The wind is getting stronger, but I steady myself and sit on the concrete edge, and close my eyes.

It’s true. From here you can’t hear the traffic anymore.